Soft robotics is a subfield of robotics that concerns the design, control, and fabrication of robots composed of compliant materials, instead of rigid links.[1][2] In contrast to rigid-bodied robots built from metals, ceramics and hard plastics, the compliance of soft robots can improve their safety when working in close contact with humans

.[2] Types and designs

3D printed model resembling an octopus

The goal of soft robotics is the design and construction of robots with physically flexible bodies and electronics. Sometimes softness is limited to part of the machine. For example, rigid-bodied robotic arms can employ soft end effectors to gently grab and manipulate delicate or irregularly shaped objects. Most rigid-bodied mobile robots also strategically employ soft components, such as foot pads to absorb shock or springy joints to store/release elastic energy. However, the field of soft robotics generally leans toward machines that are predominately or entirely soft. Robots with entirely soft bodies have tremendous potential. For one their flexibility allows them to squeeze into places rigid bodies cannot, which could prove useful in disaster relief scenarios. Soft robots are also safer for human interaction and for internal deployment inside a human body.

Nature is often a source of inspiration for soft robot design given that animals themselves are mostly composed of soft components and they appear to exploit their softness for efficient movement in complex environments almost everywhere on Earth.[3] Thus, soft robots are often designed to look like familiar creatures, especially entirely soft organisms like octopuses. However, it is extremely difficult to manually design and control soft robots given their low mechanical impedance. The very thing that makes soft robots beneficial—their flexibility and compliance—makes them difficult to control. The mathematics developed over the past centuries for designing rigid bodies generally fail to extend to soft robots. Thus, soft robots are commonly designed in part with the help of automated design tools, such as evolutionary algorithms, which enable a soft robot's shape, material properties, and controller to all be simultaneously and automatically designed and optimized together for a given task.[4]

Bio-mimicry

Plant cells can inherently produce hydrostatic pressure due to a solute concentration gradient between the cytoplasm and external surroundings (osmotic potential). Further, plants can adjust this concentration through the movement of ions across the cell membrane. This then changes the shape and volume of the plant as it responds to this change in hydrostatic pressure. This pressure derived shape evolution is desirable for soft robotics and can be emulated to create pressure adaptive materials through the use of fluid flow.[5] The following equation[6] models the cell volume change rate:

Delta P is the change in hydrostatic pressure.

This principle has been leveraged in the creation of pressure systems for soft robotics. These systems are composed of soft resins and contain multiple fluid sacs with semi-permeable membranes. The semi-permeability allows for fluid transport that then leads to pressure generation. This combination of fluid transport and pressure generation then leads to shape and volume change.[5]

Another biologically inherent shape changing mechanism is that of hygroscopic shape change. In this mechanism, plant cells react to changes in humidity. When the surrounding atmosphere has a high humidity, the plant cells swell, but when the surrounding atmosphere has a low humidity, the plant cells shrink. This volume change has been observed in pollen grains[7] and pine cone scales.[5][8]

Similar approaches to hydraulic soft joints can also be derived from arachnid locomotion, where strong and precise control over a joint can be primarily controlled through compressed hemolymph.

Manufacturing

Conventional manufacturing techniques, such as subtractive techniques like drilling and milling, are unhelpful when it comes to constructing soft robots as these robots have complex shapes with deformable bodies. Therefore, more advanced manufacturing techniques have been developed. Those include Shape Deposition Manufacturing (SDM), the Smart Composite Microstructure (SCM) process, and 3D multi-material printing.[2][9]

SDM is a type of rapid prototyping whereby deposition and machining occur cyclically. Essentially, one deposits a material, machines it, embeds a desired structure, deposits a support for said structure, and then further machines the product to a final shape that includes the deposited material and the embedded part.[9] Embedded hardware includes circuits, sensors, and actuators, and scientists have successfully embedded controls inside of polymeric materials to create soft robots, such as the Stickybot[10] and the iSprawl.[11]

SCM is a process whereby one combines rigid bodies of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) with flexible polymer ligaments. The flexible polymer act as joints for the skeleton. With this process, an integrated structure of the CFRP and polymer ligaments is created through the use of laser machining followed by lamination. This SCM process is utilized in the production of mesoscale robots as the polymer connectors serve as low friction alternatives to pin joints.[9]

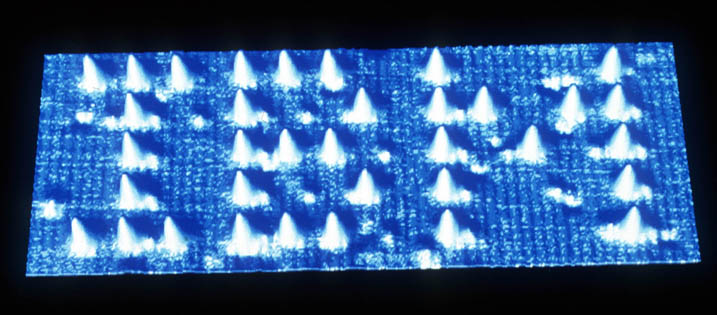

Additive manufacturing processes such as 3D printing can now be used to print a wide range of silicone inks using techniques such as direct ink writing (DIW, also known as Robocasting).[12] This manufacturing route allows for a seamless production of fluidic elastomer actuators with locally defined mechanical properties. It further enables a digital fabrication of pneumatic silicone actuators exhibiting programmable bioinspired architectures and motions.[13] A wide range of fully functional soft robots have been printed using this method including bending, twisting, grabbing and contracting motion. This technique avoids some of the drawbacks of conventional manufacturing routes such as delamination between glued parts. Another additive manufacturing method that produces shape morphing materials whose shape is photosensitive, thermally activated, or water responsive. Essentially, these polymers can automatically change shape upon interaction with water, light, or heat. One such example of a shape morphing material was created through the use of light reactive ink-jet printing onto a polystyrene target.[14]

Additionally, shape memory polymers have been rapid prototyped that comprise two different components: a skeleton and a hinge material. Upon printing, the material is heated to a temperature higher than the glass transition temperature of the hinge material. This allows for deformation of the hinge material, while not affecting the skeleton material. Further, this polymer can be continually reformed through heating.[14]

Control methods and materials

All soft robots require an actuation system to generate reaction forces, to allow for movement and interaction with its environment. Due to the compliant nature of these robots, soft actuation systems must be able to move without the use of rigid materials that would act as the bones in organisms, or the metal frame that is common in rigid robots. Nevertheless, several control solutions to soft actuation problem exist and have found its use, each possessing advantages and disadvantages. Some examples of control methods and the appropriate materials are listed below.

Electric field

One example is utilization of electrostatic force that can be applied in:

Dielectric Elastomer Actuators (DEAs) that use high-voltage electric field in order to change its shape (example of working DEA). These actuators can produce high forces, have high specific power (W kg−1), produce large strains (>1000%),[15] possess high energy density (>3 MJ m−3),[16] exhibit self-sensing, and achieve fast actuation rates (10 ms - 1 s). However, the need for high-voltages quickly becomes the limiting factor in the potential practical applications. Additionally, these systems often exhibit leakage currents, tend to have electrical breakdowns (dielectric failure follows Weibull statistics therefore the probability increases with increased electrode area [17]), and require pre-strain for the greatest deformation.[18] Some of the new research shows that there are ways of overcoming some of these disadvantages, as shown e.g. in Peano-HASEL actuators, which incorporate liquid dielectrics and thin shell components. These approach lowers the applied voltage needed, as well as allows for self-healing during electrical breakdown.[19][20]

Thermal

Shape memory polymers (SMPs) are smart and reconfigurable materials that serve as an excellent example of thermal actuators that can be used for actuation. These materials will "remember" their original shape and will revert to it upon temperature increase. For example, crosslinked polymers can be strained at temperatures above their glass-transition (Tg) or melting-transition (Tm) and then cooled down. When the temperature is increased again, the strain will be released and materials shape will be changed back to the original.[21] This of course suggests that there is only one irreversible movement, but there have been materials demonstrated to have up to 5 temporary shapes.[22] One of the simplest and best known examples of shape memory polymers is a toy called Shrinky Dinks that is made of pre-stretched polystyrene (PS) sheet which can be used to cut out shapes that will shrink significantly when heated. Actuators produced using these materials can achieve strains up to 1000%[23] and have demonstrated a broad range of energy density between <50 kJ m−3 and up to 2 MJ m−3.[24] Definite downsides of SMPs include their slow response (>10 s) and typically low force generated.[18] Examples of SMPs include polyurethane (PU), polyethylene teraphtalate (PET), polyethyleneoxide (PEO) and others.

Shape memory alloys are behind another control system for soft robotic actuation.[25] Although made of metal, a traditionally rigid material, the springs are made from very thin wires and are just as compliant as other soft materials. These springs have a very high force-to-mass ratio, but stretch through the application of heat, which is inefficient energy-wise.[26]

Pressure difference

Pneumatic artificial muscles, another control method used in soft robots, relies on changing the pressure inside a flexible tube. This way it will act as a muscle, contracting and extending, thus applying force to what it's attached to. Through the use of valves, the robot may maintain a given shape using these muscles with no additional energy input. However, this method generally requires an external source of compressed air to function. Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) controller is the most commonly used algorithm for pneumatic muscles. The dynamic response of pneumatic muscles can be modulated by tuning the parameters of the PID controller.[27]

Sensors

Sensors are one of the most important component of robots. Without surprise, soft robots ideally use soft sensors. Soft sensors can usually measure deformation, thus inferring about the robot's position or stiffness.

Here are a few examples of soft sensors:

Soft stretch sensors

Soft bending sensors

Soft pressure sensors

Soft force sensors

These sensors rely on measures of:

Piezoresistivity:

polymer filled with conductive particles,[28]

microfluidic pathways (liquid metal,[29] ionic solution[30]),

Piezoelectricity,[31][32]

Capacitance,[33][34]

Magnetic fields,[35][36]

Optical loss,[37][38][39]

Acoustic loss.[40]

These measurements can be then fed into a control system.

Uses and applications

Surgical assistance

Soft robots can be implemented in the medical profession, specifically for invasive surgery. Soft robots can be made to assist surgeries due to their shape changing properties. Shape change is important as a soft robot could navigate around different structures in the human body by adjusting its form. This could be accomplished through the use of fluidic actuation.[41]

Exosuits

Soft robots may also be used for the creation of flexible exosuits, for rehabilitation of patients, assisting the elderly, or simply enhancing the user's strength. A team from Harvard created an exosuit using these materials in order to give the advantages of the additional strength provided by an exosuit, without the disadvantages that come with how rigid materials restrict a person's natural movement. The exosuits are metal frameworks fitted with motorized muscles to multiply the wearer's strength. Also called exoskeletons, the robotic suits' metal framework somewhat mirrors the wearer's internal skeletal structure.

The suit makes lifted objects feel much lighter, and sometimes even weightless, reducing injuries and improving compliance.[42]

Collaborative robots

Traditionally, manufacturing robots have been isolated from human workers due to safety concerns, as a rigid robot colliding with a human could easily lead to injury due to the fast-paced motion of the robot. However, soft robots could work alongside humans safely, as in a collision the compliant nature of the robot would prevent or minimize any potential injury.

Bio-mimicry

A video showing the partly autonomous deep-sea soft robots

An application of bio-mimicry via soft robotics is in ocean or space exploration. In the search for extraterrestrial life, scientists need to know more about extraterrestrial bodies of water, as water is the source of life on Earth. Soft robots could be used to mimic sea creatures that can efficiently maneuver through water. Such a project was attempted by a team at Cornell in 2015 under a grant through NASA's Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC).[43] The team set out to design a soft robot that would mimic a lamprey or cuttlefish in the way it moved underwater, in order to efficiently explore the ocean below the ice layer of Jupiter's moon, Europa. But exploring a body of water, especially one on another planet, comes with a unique set of mechanical and materials challenges. In 2021, scientists demonstrated a bioinspired self-powered soft robot for deep-sea operation that can withstand the pressure at the deepest part of the ocean at the Mariana Trench. The robot features artificial muscles and wings out of pliable materials and electronics distributed within its silicone body. It could be used for deep-sea exploration and environmental monitoring.[44][45][46] In 2021, a team from Duke University reported a dragonfly-shaped soft robot, termed DraBot, with capabilities to watch for acidity changes, temperature fluctuations, and oil pollutants in water.[47][48][49]

Cloaking

Soft robots that look like animals or are otherwise hard to identify could be used for surveillance and a range of other purposes.[50] They could also be used for ecological studies such as amid wildlife.[51] Soft robots could also enable novel artificial camouflage.[52]

Robot components

Artificial muscle

This section is an excerpt from Artificial muscle.

Artificial muscles, also known as muscle-like actuators, are materials or devices that mimic natural muscle and can change their stiffness, reversibly contract, expand, or rotate within one component due to an external stimulus (such as voltage, current, pressure or temperature).[53] The three basic actuation responses– contraction, expansion, and rotation can be combined within a single component to produce other types of motions (e.g. bending, by contracting one side of the material while expanding the other side). Conventional motors and pneumatic linear or rotary actuators do not qualify as artificial muscles, because there is more than one component involved in the actuation.

Owing to their high flexibility, versatility and power-to-weight ratio compared with traditional rigid actuators, artificial muscles have the potential to be a highly disruptive emerging technology. Though currently in limited use, the technology may have wide future applications in industry, medicine, robotics and many other fields.[54][55][56]

Robot skin with tactile perception

This section is an excerpt from Robotic sensing § Types and examples.

Examples of the current state of progress in the field of robot skins as of mid-2022 are a robotic finger covered in a type of manufactured living human skin,[57][58] an electronic skin giving biological skin-like haptic sensations and touch/pain-sensitivity to a robotic hand,[59][60] a system of an electronic skin and a human-machine interface that can enable remote sensed tactile perception, and wearable or robotic sensing of many hazardous substances and pathogens,[61][62] and a multilayer tactile sensor hydrogel-based robot skin.[63][64]

Electronic skin

This section is an excerpt from Electronic skin.

Electronic skin refers to flexible, stretchable and self-healing electronics that are able to mimic functionalities of human or animal skin.[65][66] The broad class of materials often contain sensing abilities that are intended to reproduce the capabilities of human skin to respond to environmental factors such as changes in heat and pressure.[65][66][67][68]

Advances in electronic skin research focuses on designing materials that are stretchy, robust, and flexible. Research in the individual fields of flexible electronics and tactile sensing has progressed greatly; however, electronic skin design attempts to bring together advances in many areas of materials research without sacrificing individual benefits from each field.[69] The successful combination of flexible and stretchable mechanical properties with sensors and the ability to self-heal would open the door to many possible applications including soft robotics, prosthetics, artificial intelligence and health monitoring.[65][69][70][71]

Recent advances in the field of electronic skin have focused on incorporating green materials ideals and environmental awareness into the design process. As one of the main challenges facing electronic skin development is the ability of the material to withstand mechanical strain and maintain sensing ability or electronic properties, recyclability and self-healing properties are especially critical in the future design of new electronic skins.[72]

Qualitative benefits

Benefits of soft robot designs over fully conventional robot designs may be lighter weight -- heavy payloads are expensive to launch -- and increased safety -- robots may work alongside astronauts.[73]

Mechanical considerations in design

Fatigue failure from flexing

Soft robots, particularly those designed to imitate life, often must experience cyclic loading in order to move or do the tasks for which they were designed. For example, in the case of the lamprey- or cuttlefish-like robot described above, motion would require electrolyzing water and igniting gas, causing a rapid expansion to propel the robot forward.[43] This repetitive and explosive expansion and contraction would create an environment of intense cyclic loading on the chosen polymeric material. A robot in a remote underwater location or on a remote planetary body like Europa would be practically impossible to patch up or replace, so care would need to be taken to choose a material and design that minimizes initiation and propagation of fatigue-cracks. In particular, one should choose a material with a fatigue limit, or a stress-amplitude frequency above which the polymer's fatigue response is no longer dependent on the frequency.[74]

Brittle failure when cold

Secondly, because soft robots are made of highly compliant materials, one must consider temperature effects. The yield stress of a material tends to decrease with temperature, and in polymeric materials this effect is even more extreme.[74] At room temperature and higher temperatures, the long chains in many polymers can stretch and slide past each other, preventing the local concentration of stress in one area and making the material ductile.[75] But most polymers undergo a ductile-to-brittle transition temperature[76] below which there is not enough thermal energy for the long chains to respond in that ductile manner, and fracture is much more likely. The tendency of polymeric materials to turn brittle at cooler temperatures is in fact thought to be responsible for the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, and must be taken very seriously, especially for soft robots that will be implemented in medicine. A ductile-to-brittle transition temperature need not be what one might consider "cold," and is in fact characteristic of the material itself, depending on its crystallinity, toughness, side-group size (in the case of polymers), and other factors.[76]

International journals

Soft Robotics (SoRo)

Soft Robotics section of Frontiers in Robotics and AI

Science Robotics

International events

2018 Robosoft, first IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics, April 24–28, 2018, Livorno, Italy

2017 IROS 2017 Workshop on Soft Morphological Design for Haptic Sensation, Interaction and Display, 24 September 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada

2016 First Soft Robotics Challenge, April 29–30, Livorno, Italy

2016 Soft Robotics week, April 25–30, Livorno, Italy

2015 "Soft Robotics: Actuation, Integration, and Applications – Blending research perspectives for a leap forward in soft robotics technology" at ICRA2015, Seattle WA

2014 Workshop on Advances on Soft Robotics, 2014 Robotics Science and Systems (RSS) Conference, Berkeley, CA, July 13, 2014

2013 International Workshop on Soft Robotics and Morphological Computation, Monte Verità, July 14–19, 2013

2012 Summer School on Soft Robotics, Zurich, June 18–22, 2012

In popular culture

Chris Atkeson's robot that inspired the creation of Baymax[77]

The 2014 Disney film Big Hero 6 features a soft robot, Baymax, originally designed for use in the healthcare industry. In the film, Baymax is portrayed as a large yet unintimidating robot with an inflated vinyl exterior surrounding a mechanical skeleton. The basis of Baymax concept comes from real life research on applications of soft robotics in the healthcare field, such as roboticist Chris Atkeson's work at Carnegie Mellon's Robotics Institute.[78]

The 2018 animated Sony film Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse features a female version of the supervillain Doctor Octopus that utilizes tentacles built with soft robotics to subdue her foes.

In episode 4 of the animated series Helluva Boss, inventor Loopty Goopty uses tentacles with soft robotics tipped with various weapons to threaten the members of the I.M.P into murdering his friend, Lyle Lipton.